Tuesday, October 24, 2006

Thursday, October 05, 2006

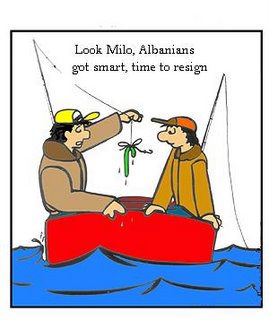

No More Fishing in Malësia

Nutritionists say that fish is “brain food,” that by consuming small portions at least once a week it increases one’s memory significantly. As a result, it would be fitting that fish be a required dietary alternative for those who experience short-term memory loss. This assertion can be safely attributed to Montenegro’s outgoing Premier, Milo Djukanovic, who for the past decade has seemed to forget the promises he made to Malësia, promises that he hoped Albanians would also forget.

Let us not forget that it was our popularly-elected Milo that promised Malësia the fruits of fortune, progress, stability and proliferation in 1997; it was Milo that pledged to Malësia comprehensive forms of self-determination and self-representation in 2002; it was Milo that assured Malësia enhanced minority rights, economic development, political accommodation, civic-ness and civility in 2004; and who can forget when in 2006 Milo promised Malësia the world by granting her an autonomous Commune with all the benefits of the previous 21 before her?? Promises they were, realities they were not.

In fact Malësia should not forget any time soon, because like any good Fisherman you have to attach the right bait on a fishing line, throw it out into the waters and wait for something to bite. Milo proved to be a Master Fisherman – for the bait he chose to cast into the waters of Malësia from 1997-2007 fetched him a lot of quality fish; and with every new season Milo would select his bait carefully so he would have enough to show the international community that the fish in Malësia bite every time he throws bait their way.

But something strange happened in September 2006: The fish stopped biting. Perhaps they got sick of the same bait, or was it the same lies? The fish craved a new flavor, something that would keep their bellies full without getting them hooked and taken away from their autonomous waters; perhaps the fish decided to eat from their own territory and not swim outside their boundaries where danger always persisted, where so many of them were caught and eaten, often depleting the waters of the best and tastiest fish of them all.

This scared Milo, because no fish means no power, and no power in the Balkans means the start to a political downfall. Even with the fish he caught in the past, problems will come to light. We know what happens to fish out of water, they flip, twist and jump frantically until they are let back into their environment, and by keeping them locked up for too long, they attract a foul smell that will poison anyone that dares to taste it. Milo understands that the 15 fish he is keeping locked up in Podgorica will eventually destroy him, and the only way to prevent harm is to let them back into their waters.

Today we see “No Fishing” signs all over Malësia; not because the fish are no good, but because it is time to remind the new Fisherman that the waters of Malësia are forbidden for fishing anymore, and those that dare to cast a line into her waters will be pulled in and drowned!

The Old Man from Malësia

An old Albanian lives in Malësia close to Tuz. He would love to plant potatoes in his garden, but he is old and weak. His son is in college in Detroit, so the old man calls him on his cell phone.

"Beloved son, I am very sad, because I can't plant potatoes in my garden. I am sure if you were here you would help me dig up the garden."

The following day, the old man receives a voice-mail message from His son at 3:45 p.m.:

"Beloved father, please don't touch the Garden. It's there that I have hidden ‘the THING’, Love Besnik".

At 4:02 p.m., the Montenegrin police, along with the special anti-terrorist unit, UDB-a, and the national army, visit the house of the old man, take the whole garden apart, search every inch, but can't find anything. Disappointed they leave.

A day later, the old man receives another voice-mail message from his son:

"Beloved father, I hope the garden is dug up by now and you can plant your potatoes. That's all I could do for you from here, Love Besnik."

Wednesday, October 04, 2006

Djukanovic Resigns, But Corruption Continues

Montenegrin Prime Minister Milo Djukanovic declared Tuesday that he will resign his post despite his coalition's victory in last months parliamentary elections.

Although President Filip Vujanovic stated that Djukanovic is resigning for "personal reasons" many believe that his decision to leave after 15 years in power is largely due to the growing unrest surrounding the Albanian region of Malesia and the failure to bring unity and cohesion between ethnic and religious groups in Montenegro.

His record as President and Prime Minister has been plagued with problems since he took office. In Italy prosecutors are still investigating allegations that Djukanovic was a ring-leader in a multi-million dollar cigarette smuggling racket. This stemmed when in 2002 the European Union accused tobacco giant R.J. Reynolds in a lawsuit of selling black-market cigarettes to drug traffickers and mobsters, helping them launder profits from their illegal activities.

Among the other allegations in the lawsuit, RJR moved its cigarettes through the Balkans in the 1990s by means of illicit payments to corrupt government officials, including Milo Djukanovic, and the deceased former head of the Montenegro's Foreign Investment Agency, Milutin Lalic.

The suit said payments came from a company founded by Italian organized crime figures that had the official sanction of the investment agency and operated under the protection of Djukanovic. The company, Montenegrin Tabak Transit, was granted exclusive rights to move cigarettes through the Port of Montenegro, and over time made millions of dollars in payments to members of the Yugoslav federal government and Montenegrin regional governments, including Djukanovic and Lilic, the lawsuit states.

It says RJR executives and distributors were well aware that such "licensing fees" were being paid to facilitate the movement of their brands. They "traveled to Montenegro on a regular basis to inspect their cigarettes and service their customers and, as such, were well aware of these practices," the lawsuit states.

According to European press reports, Italian authorities had opened a criminal investigation into alleged involvement by Djukanovic with Mafia-run smuggling operations.

Also suspect is his quick rise to fortune, where Djukanovic and everyone close to him have become suspiciously rich over the years. Since he took office, Montenegro bacame a haven for tycoons wishing to launder money through fraudulant banks where anyone with $10,000 could create their own bank and funnel bogus money without undergoing verification checks.

In Montenegro you can create your own offshore bank for only $9,999, in eight weeks or less and without a background check.

The offshore status of the banks means their foreign owners benefit from tax breaks, exemption from currency controls and confidentiality (Wired News).

Senate investigators (including Carl Levin of Michigan who in 2001 spoke on this behalf in a Senate committee hearing) who say many large U.S. banks have unwittingly become conduits for dirty foreign money, see the ads as a new money-laundering danger because the "personal" banks may offer links to accounts at American institutions.

The new banks licensed by Montenegro, for example, are touted as offering correspondent accounts at the national Bank of Montenegro, which in turn is said to have accounts with major banks in Switzerland and other countries.

Today Djukanovic is facing growing pressure from ethnic Albanians in the Malesia region, who deamnd he pay more attention to minority rights and adhere to appeals for greater self-representation in all spheres of life. The arrests of Albanians made last month in Tuz also triggered an outcry from Albanians in the Diaspora calling for Djukanovic to step down after Albanians were rounded up, beaten and tortured just 24 hours before national and local elections were to take place. Many still believe that these actions were politically motivated to scare Albanians from participating in those elections.

Sunday, October 01, 2006

Terrorism From Above

This masked gunman participated in the violent raids in the Albanian-dominant region of Malesia where he and dozens of other policemen viciously beat, arrested and tortured numerous Albanians for alleged acts of terror. To this day no evidence has linked any of those arrested to any crimes, however the abuses continue inside the prison walls and in the villages surrounding Tuz, where daily life has changed considerably. Fear of state suppression is once again making a comeback in this former Yugoslav republic, which has minorities fearing that the independent Montenegro that they voted for has turned the tables against them.

These were the same units that operated under Slobodan Milosevic during the wars with Croatia, Bosnia and parts of Kosova, which left thousands dead and many more displaced. Today Montenegro has created an atmosphere that is damaging inter-ethnic relations, something that has plagued the Balkans for the past 15 years and now continues via the political apparatus in Podgorica.

Podgorica's control of all media outlets has enabled these illegal interrogations to proceed unchallenged, given that any media detractors willing to challenge the legitimacy of the arrests will either be permanently shut down or arrested for "treason."

Moreover, because Montenegro does not have an independent judiciary, one that repects the rule of law in the domestic and international realm, the chances that those being held in jail to receive a fair and speedy trial is nullified. Any and all evidence brought before them, however fabricated it will be, will not be dismissed but used to levy the harshest penalties available. This is an incredulous contradiction to the postulates of democracy and democratic transition. It is imperative that a state claiming to practice democratic traditions and appealing to join the family of Europe must also exercise an independent judiciary that has no influence from other state institutions (ie, Parliament, PM, etc.). This is not the case in Montenegro; what we have in Podgorica is a parallel government that shadows that of Belgrade during the era of the communist party.

State terrorism thus is nothing new in Montenegro. Its hold on the Albanian minority population through oppressive and fear tactics is crucial for them. Over the past several months Albanian nationalism has finally made its way from Kosova to Malesia, evidenced by the unified campaigns to elect members of local parties and oust those that have hindered their progress and development. This show of force has caught the attention of Podgorica and has caused discomfort in Djukanovic's party; the fear of an Albanian (political and social) uprising where the several regions of Malesia e Madhe would socially, ideologically and politically unite would spell trouble in the eyes of Montenegrins. The prospect of an "Ethnic Albania" has caused many sleepless nights in Podgorica, and those prospects drew a bit closer on September 10th when Albanians catapulted their own representatives into Parliament and local offices for the first time ever.

What is important now is to see how Podgorica handles two issues, (1) the victory of Albanians in Malesia with representatives in Parliament and in the urban municipality, and (2) the handling of the prisoners. International pressure on the latter will continue to mount, and Podgorica must be very careful on how they act during their "face-saving" plans.

Viktor Ivezaj -- "Standards Before Referendum: The Content of Montenegro’s Future Status Will Depend From the Approach of Majority Towards Minorities"

Commentary by Viktor N. IVEZAJ

Department of Political Science

Wayne State University

Detroit, Michigan USA

viktor.ivezaj@wayne.edu

29 March 2006

If history has taught us anything over the past fifteen years, we now know that if a state wants to hold its entire society together, the majority must acknowledge the right of minorities to be treated equally both as individuals and as communities. These lessons have demonstrated that effective representation of minorities on all levels of decision-making, the existence of strong self-governments with minority representatives or special minority self-governments, and even power-sharing within the institutional state structure, will improve the deficiencies of democratic, multiethnic states. Throughout Eastern Europe, the new wave of democratic transition is coming to mean the acceptance of the majority’s decisions by the minority, a now popular concept gaining momentum throughout the European Union and suddenly making its presence felt in the former communist states of Eastern Europe, including Montenegro.

Developments in Montenegro have triggered discussions as to whether the country is prepared to ride this wave of democracy and shed away its turbulent past. The focal point of these debates have largely centered on the fate of the Belgrade Agreement (which recently celebrated its third birthday) and whether it should be sustained or dissolved. Contrary to Serbia’s pro-union aspirations, Montenegro is campaigning heavily to break the bitter marriage and pursue independence as the only remedy for political and economic success, a unilateral move that has drawn criticism from EU officials, opposition parties in parliament, and multi-ethnic groups throughout this tiny republic. Although success will largely depend on Montenegro’s capacity to strengthen and manage its economic and governing institutions, including its community development, and local governance, it will also require observance to the growing demands of its multiethnic citizenry to be incorporated into its political, economic, social and civic processes. To declare that Montenegro has realized these objectives would be an exaggeration, to say the least. In fact, nowhere else has it failed more miserably in its sociopolitical reforms than its handling of minority rights, and without exception the Albanians in the southern region of Malësia e Madhe continue to be victims of neglect, disenfranchisement, and assimilation.

Without dedicating much thought into its dissipating inter-ethnic relations, and consequences that may arise thereof, Montenegro’s political elites have decided to ignore the warning signs from the agitated opposition and rush for a referendum while blindly assuming that all of its domestic tribulations will be swept under the rug. One of the most surprising moves has been the reluctance from Podgorica’s politicians to step back and assess its handling of Albanian affairs before it continues in what it falsely believes to be a pacified situation with its largest ethnic group. Although the outcome of the referendum will draw much dispute from the large Serbian and Bosniak communities, it is also worth noting that failure to also appease the demands of its multi-ethnic citizenry preludes a much-feared consequence that has the international community fearing the worst: a disputed outcome that may trigger a movement to split the country geographically along ethnic lines. The remedies to prevent this from happening were carefully outlined in Vienna, but the Solana and Lajcak proposal that suggests the country be allowed to secede from the federation if 55 percent of voters choose independence and 50 percent of the people entitled to vote take part in the vote is primarily designed to maintain the marriage between Montenegro and Serbia, given that it is nearly impossible for this divided country to muster enough votes away from the opposition. But the logistics of the referendum are only part of Montenegro’s growing pains. In addition to the politics being played out in Podgorica, a growing concern is developing south of the capital where a disenfranchised Albanian minority is seeking alternatives to the failed sociopolitical and economic policies that have for so long stagnated their development and continues to threaten their very existence.

In the Albanian community in and around Tuz, or Malësia e Madhe, a substantial level of political and administrative decentralization will be a decisive component in reassuring the nearly 13,000 Albanians that they have a place in Montenegro’s future, regardless if the referendum passes or fails. The lack of responsiveness to Albanian demands for an urban restructuring plan where Malësia would be recognized as a distinct municipality has drawn sharp criticism from Albanian political elites in Tuz where countless demands have been submitted calling for reforms in education, employment, healthcare, housing and criminal justice. Albanian elites and political representatives have warned Podgorica that their reluctance to address these demands will contribute to the growing discontent towards the majority and threaten to alienate them from the political process. With these appeals entering deaf ears, intellectuals have decided that under the decrees of international and domestic laws, the most feasible solution to the problems facing Albanians today is to empower local citizens to handle their own affairs, which means decentralizing Podgorica and creating a separate commune that would be better suited to handle the most salient issues pertaining to Albanians. Montenegro’s proposal of last year’s Capital City Bill, which suggested that Tuz remain a sub-unit of Podgorica, was largely considered a failed scheme that was designed to temporarily “hush” local Albanians until the referendum was passed. The adverse effect of this move have caused Albanians to become skeptical of Podgorica’s motives, and as a result has discouraged Albanians from involvement in the political decision-making processes, which could be detrimental for the majority party in the days leading to the referendum.

One way that Montenegro can successfully deal with such diversities in its society is by lessening control from the center (Podgorica) and assigning more institutional and political control at the local level (Malësia). A constitutional structure where Albanians have a veto in policies that affect them most would alleviate some of the problems between majorities and minorities. The significance of decentralization has gained so much attention lately that even the negotiations on the future status of Kosova will depend on empowering local communities to participate more in all bodies of the government, especially the legislative branch and police.” Kosova’s Minister of Local Government, Lutfi Haziri, announced recently that local government is an important feature of a state’s political structure, and rightfully asserts, “it will be a serious offer [local-government control]…to the Serb ethnic community, so they can integrate and become part of the process and lead on the local administration level. This means they would govern on the local level and handle the organization of life and services.” In Macedonia, the conflict that almost thrust the country into all out civil war was diverted under conditions that the Albanian minority have increased power in areas they occupied as a majority, thus much of Macedonia’s municipalities were geographically restructured to compliment its ethnic makeup. These regional measures clearly demonstrate the direction the international community is embarking upon in efforts to maintain peaceful transitions of government, which renders the situation in Malësia perplexing when considering the developments taking place in regions that were once marred by ethnic war.

In Montenegro, the politics of municipalities have been made out to be so complex that even realignment specialists are confused as to how to depict them. Most of the municipalities in Montenegro are considerably large and disproportionate when compared to other European nations, where inhabitants range from 2,947 in the municipality of Savnik to 169,132 in Podgorica. According to the 2003 census the ethnic composition of Albanians in Montenegro was 47,682 (7.09%), and in the Podgorica municipality it was 12,951, nearly all living in the Malësia region. Albanians do not see the question of decentralization as being purely in the interest of Albanians, but of crucial importance for all ethnic communities, for overall democratization of Montenegro and for efficient institutional minority protection.

Throughout their appeals for a municipality, Albanians have maintained they do not imagine themselves as an "independent entity" but want to be part of a Montenegro where representation of all groups at all levels of public administration and government are at the core of any power-sharing arrangement, which is an essential aspect of their guaranteed rights as a minority. Exercising freedom through participation in public affairs is extremely important, because it gives people a personal interest in thinking about others in society. Local self-government forces the people to act together and feel their dependence on one another. These demands fall under the sphere of European laws specifically designed to protect ethnic minorities. The European Charter of Local-Self Government, which Montenegro is a signatory, clearly defines the laws regulating conditions and procedures for the foundation, abolition and integration of municipalities. When assessing these requirements, it is clearly obvious that Malësia meets all the necessary requirements for classification into a separate commune.

The starting point is historical development and tradition, which can be done after a local community [in this case Malësia] has declared its interest to do so. According to Montenegro’s Constitution and European laws attributed to local self-government, “a municipality represents a geographically and economically integrated entity for the local people, which is reflected in the integration of urban areas, the number of inhabitants, the organization of the services of immediate interests for local people, gravitation towards the center, the development and ecological conditions of the area and other questions important for the citizens of a certain area and for the realization of the mutual interests and needs.” By looking at it from this context, it is an enigma why Malësia has remained without a municipality for so long. However, most urban analysts, and including myself, would argue that local government institutions would help solve only some of the problems facing Albanians in Malësia, and that a broader analysis reveals deeper complexities that exist in society that are beyond the scope of a commune.

Albanians need not be deceived into thinking that a commune will solve all their problems. In the municipality of Ulqin, where Albanians make up 85% of the population, the head of police and head of the municipal court has never been held by an Albanian. As such, a commune should be welcomed as a means to overcoming the various difficulties facing them at the local level, and not as the ultimate end to their problems. The danger presents itself as a double-edge sword: First, it is under the nature of negotiations that Podgorica may bring forth. Montenegro’s political elites should refrain from using the granting of a commune as an “end all” bargaining chip, but instead think of the Albanian problem as a Montenegrin problem. Isolating Malësia will only contribute to the growing disparities in economic, political and social development. Second, the bigger troubles that face Albanians go beyond anything a commune can solve, and they lie within the enclaves of the community.

First, the bigger crisis facing Albanians in Malësia is not the reluctance of Podgorica to grant them more control of their sociopolitical affairs via a commune; instead their dire situation is linked with the sharp cleavages that exist inside Albanian communities. When assessing the treatment of Albanians in communities throughout the Balkans, Albanians in Malësia have been the least discriminated against, and as a result they never considered it a burning issue to challenge the status quo. With the absence of an Albanian national awakening in Montenegro, the cleavages have continued to create sharp divisions between those Albanians, on the one hand, insisting that the status quo not be disrupted and those, on the other, realizing that the status quo is a pre-determined strategy to completely wipe out an entire people by forced assimilation and emigration. Whether these claims are correct or not, what it is true, however is that some of the most talented Albanian minds from Malësia have opted to focus their intellectual strengths for the Montenegrin cause, where they have been on record to support policies that have obstructed development in the very places they were nurtured. Podgorica has consistently rewarded these sympathizers by appointing them to high-ranking positions, a practice that sounds all too familiar when thinking back to the days of Ottomans rule. Those intellectuals that have refused to be recruited inside the corruptive circles have decided to either initiate change from within or emigrate abroad and consequently never return. The question that is often taken for granted nowadays is one that needs to be revisited: “What does it mean to be Albanian?” But seeking the answer to this question may produce disturbing affects because when the Albanian consciousness finally awakens, it will be startled to realize that what it means to be Albanian in Malësia has suddenly taken Slavic nuances.

Second, Albanians must recognize that false convictions attached to the popular thought that an independent Montenegro will improve their socio-economic and political status are misguiding. With or without Serbia, the Albanian situation will not improve unless the Montenegrin parliament takes the initiative to seriously draft proposals outlining projects designed to specifically expand Albanians’ role in society. Gjukanovic’s primary goal is to secure his position of power, and it is within his best interest to maintain the status quo in a way that will not threaten his party’s hold of the republic. Keep in mind that the question of the referendum did not materialize as a will of the people, but the will of Montenegrin political leaders led by Gjukanovic, who thus wants to extend his unlimited power with the alleged will of the people. His campaign for independence centers on the hope that the international community will accept Montenegro into the family of western democracies once it has done away with Serbia and her treacherous past. This is the same rhetoric he is using to lobby Albanians for their votes in the coming referendum, including promises similar to those he made during his re-election bid for president in 1997 where Albanians were decisive in his slim 5,000 vote victory over Bulatovic. Nevertheless, Albanians continued to be underrepresented in all spheres of public employment, where, according to the Helsinki Committee For Human Rights in Serbia, “only 0.03%--0.05% of Albanians are employed in state bodies and public services in Montenegro.” What the international community needs to realize is that no civic programs have been initiated to alleviate the disproportionate representation of Albanians in the public sector, “despite the fact that the Constitution of the Republic of Montenegro clearly specifies that members of minorities should be employed in civil services in proportion with their share in the total population.”

Third, existing institutions must be modernized to operate within the framework of the federal republic and under European guidelines. One of the most noticeable disparities in Montenegrin institutions is the lack of minority representation in the police, judiciary, bureaucracy, media and academia. One of the key anecdotes that Montenegro must implement is how to resolve the dismal social conditions and ethnic relations that are always in danger of spinning out of control. Programs in civic leadership and law enforcement need to be introduced in the Albanian community so that citizens at the local level can participate in the criminal justice system and not be a victim of it. Albanian media outlets should be extended outside the Albanian viewing areas in an effort to illustrate the cultural diversity to those unfamiliar with the uniqueness of Albanian culture and tradition, a project that could perhaps replace the majority public’s negative perceptions that are usually associated with ignorance and lack of contact. Academic programs at the university level where Albanian cultural studies are offered as a course credit would strongly contribute towards familiarizing tomorrow’s leaders with the history and distinctiveness of the largest minority group in society. The reality is, Albanians are not going anywhere, and their continued presence and contribution in all spheres of society deserves recognition.

Fourth, the most dangerous feature of Montenegro’s government is the corruption of individual office holders and government agencies. Let us not forget that many of the conflicts Yugoslavia endured in her history were identity-based and manipulated by cynical politicians wishing to reach their own ends. Thus the bloody struggles that raged in Bosnia and then again in Kosova were kindled by politicians like Milosevic who sought to increase their personal power. Today, those memories are difficult to erase because the ideologies of the old regime are still alive and functioning under the guise of Gjukanovic’s so-called “democratic” transition, a misguided ideology that has thus far fooled the international community into thinking that the status quo does not threaten peace and security in the region. It is for this reason that minorities are cautious to accept any change that does not include them as active participants in the political system. By suppressing minority participation in spheres of government activity, the risk of social and political upheaval is eminent.

On the other end of this political cauldron exists a much more puzzling aspect of corruption that is even harder to comprehend by western democratic standards. Much of the grievances by Albanians have gone unnoticed by their own elected political representatives, most notorious being the head of the Albanian Political Party, Ferhat Dinosha. From a democratic standpoint, the fact that Dinosha was popularly elected into office demonstrates that he deservingly represents his constituency, a reality that cannot be denied. If he deviates from the will of the electorate and legislates in a way that undermines his constituents’ consent, the most logical remedy provided by democratic theory is to remove him from office via the next electoral cycle. To argue anything contrary to this is useless because it defies popular belief that an elected politician can legislate against the wishes of the very same people that put him in office. The problem that also arises is where to find competent candidates that would (legitimately) win the consent of the people and generate enough votes to pull ahead of the Dinosha and Gjukanovic charade. Now that Dinosha has revealed his vulnerability to Albanians and Montenegrins alike, his continued stay will only strangle any attempt for Malësia to move forward since his legitimacy has forever been tainted. If the coming elections fail to upend this controversial figure, then Malësia seems to have been depleted of candidates capable enough to successfully represent the will of the people. Regardless of one’s profession, it is absurd to believe that legislating as an Albanian in a Slav-dominant parliament is anything but easy, but that should not be a deterring factor given that even one vote in parliament can be so vital that it can determine “who gets what, when, and how;” otherwise Gjukanovic would not lobby Dinosha for his vote each time legislation is introduced that might cause an adverse reaction in Malësia. In this context, it is important for Gjukanovic to secure the “Malësia vote” so that he can defend any controversial legislation as an agreed upon policy accepted by Malësia’s duly elected representative. As long as Dinosha continues to wear the glove that keeps him “warm,” the hand will always move in the direction the glove wants it to.

Finally, international law does not favor the current condition of Albanians in Montenegro. Unless for the improbable chance of genocide, ethnic cleansing or massive repressive tactics from the state, international and European law will be slow to hear challenges that it believes should be handled at the local level. The Council of Europe in its 1995 Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, in compliance with the OSCE standards, became a requirement for a country to “join the West,” and in particular to join the European Union. However, there has been far less agreement about what exactly these standards should be. There is no debate of how to resolve claims relating to territory and self-government or how to allocate official language status. Montenegro has claimed that it fully respects these standards, but yet continues to centralize power in such a way that all decisions are made in forums controlled by the dominant national group. What is more disturbing is that Montenegro has also prearranged higher education, professional accreditation, and political offices so that members of minority groups must linguistically assimilate in order to attain professional success and political influence. Hence, these legal norms do not address the clash between minority self-government claims and centralizing state policies that generated the destabilizing ethnic conflicts in the first place. For these reasons the prospects for change are more likely to achieve an effect by either (1) utilizing local political channels where grievances are received and resolved in a manner that does not discriminate on the basis of an ethnic and/or religious group, or (2) collectively organizing the community to publicize the grievances by way of protests, rallies, meetings, and so on. Because Albanian culture has now shown signs of being embedded in structural change, the social conditions in Malësia appear ripe for collective action. The demonstrations that took place in Tuz last October and again on 21 March should have caught no one by surprise, and should have signaled a warning to Podgorica that the Albanian question needs immediate inquiry. In the same vein, the Albanian Diaspora organized its own demonstrations at a much grandeur style in Detroit and Washington, DC. The Albanian-American Association in Detroit, the largest and most assertive organization in the United States dealing specifically with Albanian rights issues in Montenegro, was conceived with a purpose of highlighting the disparities and troublesome human rights policies that continue to be practiced by Montenegro’s political elites. Their success has earned the attention of numerous Washington officials and non-governmental organizations, which are beginning to realize that an independent Montenegro does not necessarily spell a democratic Montenegro. With the referendum fast approaching, Albanians in Malësia are expressing a desire once again to petition the government en-masse in an effort to elevate their grievances beyond the local level.

On the other hand, let us not be fooled, Montenegro is no Kosova – where the rallying cry was well-defined for the international community. Nonetheless, what is happening in Malësia today takes on similar connotations to what played out in the 1990s. The social, economic, political and civic repressions have reached a point in Malësia where citizens are forced to abandon their ancient homeland for a better life abroad. There should be no wonder then why there are more Albanians from Montenegro living in Detroit than there are in all of Montenegro. This form of “bureaucratic ethnic cleansing” has drastically changed the composition of Albanians, where once densely populated lands such as Koja and Trieshi are now virtually emptied. The long-term effects have taken its toll; the Malësia e Madhe that was once saturated with Albanians from the Gruda, Hoti, Trieshi, Koja and Luhari regions is now being contested by Montenegro as only consisting of Gruda and Hoti, a dangerous assertion that has many Albanians furious. Any attempt to divide these historic Albanian lands under any administrative or geographic circumstances threatens to undermine any reasonable negotiations between Podgorica and Malësia.

An additional element to this argument has been the trouble dealing with war refugees. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, there were 28,493 displaced persons in Montenegro as of August 2004. Out of this number, 4,400 are Roma; 6,483 Serbs; and 4,074 Muslims. The UNCHR also claims that nearly 50,000 are living throughout Serbia and Montenegro who have not been officially registered, and who would thus have to be added to the overall figure. A large number of these displaced persons have crossed over into Malësia and settled in the Konik and Vrella regions and are currently funded by the Montenegrin government. These majority Bosnian-Muslim settlements have significantly destabilized the ethnic composition of the region where the Albanian communities come in danger of falling below the majority threshold. Under these conditions, Albanian historic settlements are in jeopardy of falling under the ownership of members of a foreign group. Any deliberations on Malësia’s future must incorporate the question of how to deal with displaced persons.

Balkan history has clearly demonstrated that when minorities feel powerless and left out of the power-sharing arrangement of society, they will try to gain local autonomy and break away in an effort to change their minority status into a majority. As a consequence, the longer minorities feel excluded, the stronger those aspirations become. These are precisely the concerns that continue to cause havoc to international observers and scholars seeking to find solutions to how to deal with bastions of repressive governments. Montenegro is no exception. Many of the issues commented here have been subject to scholarly research and have begun to make their way to international conferences around the globe. Research on the Albanian situation in Montenegro was presented last summer at the First International Global Conference in Istanbul, Turkey, where a special session dealing with minorities in Eastern Europe included a paper entitled, “Political Integration of the Albanian Minority in Post-Communist Montenegro.” In a similar vein, some of the themes presented in this commentary have been prepared for the upcoming 20th World Congress in Fukuoka, Japan in a paper entitled, “Failing to Meet Europe’s Demands on Minority Rights: The Case of Montenegro’s Albanians.” The research examines Montenegro’s policies towards its Albanian minority and touches upon three key issues that will be vital in assessing its progress towards European integration: (1) the role of political elites, parties and institutions, (2) political infrastructure: decentralization and municipal government, and (3) the influence of nationalism and ethnicity on political representation.

But academic inquiry into such areas only help us begin to understand the vast problems that exist in societies, it does not provide a clear-cut solution. For Albanians and Montenegrins alike, the first step is to agree what the problems are that exist (where some have been briefly touched upon here), and then a decision has to be made on how to tackle them. Nonetheless, if Albanians do not consent that infringements such as the right to use their language in courts and local administration; the funding of minority schools, universities, medical clinics, and media; the extent of local or regional self-government; the guaranteeing of legitimate political representation; and the prevention on settlement policies intended to engulf minorities in their historic homelands with settlers from the majority group is not reason enough to stand up and demand protection, then this author can assert that assimilation has achieved its ultimate goal, and Malësia e Madhe north of the Albanian border has vanished. If Montenegro does not consider the consequences of this evolution detrimental to its future, then history has taught her nothing, and it will continue to repeat itself in the most profound and catastrophic ways.

Albanians in Detroit Protest Against the Brutality and Torture of Albanians in Montenegro!

DETROIT, MICHIGAN, September 29, 2006 – Today the Albanian-American Association “Malёsia e Madhe” in conjunction with the Albanian communities of Greater Detroit, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois and New Jersey came together to protest the cruel and inhumane treatment of the ethnic Albanians of Montenegro, where just three weeks ago, in the Albanian-dominant region of Malёsia, Albanians became victims of brutal state aggression that has not been witnessed since the conflict in Kosova.

In the early morning of September 9th masked gunmen from the Montenegrin special police units were ordered, without warning, to break into the homes of several Albanian families while they slept, and arrest individuals that according to P.M. Milo Djukanovic “posed a threat to national security.” In fact, before the arrests were made and without examining one piece of evidence against them, Podgorica had already labeled these people as “terrorists”, an accusation that has caused havoc throughout the country.

During their round-up procedures, police severely punished those who questioned their motives by beating them in their own homes where no one was spared – the victims included the elderly and women. Included in the arrests were three U.S. citizens that were in the country visiting family.

In prison, the detainees were beaten and tormented on a daily basis. No access was given to family or outside sources, Montenegro controlled all the media reports, which continue to stress to this day that those arrested were planning to participate in terrorist acts against the state.

However, no evidence has been brought forth to this point, no witnesses to these accounts have been named, and every Albanian detained continues to deny their involvement in these fallacious accusations.

In the mean time, the detainees continue to be harassed and persecuted for crimes they did not commit.

The following is a list of the innocent prisoners being wrongfully charged for crimes they did not commit:

1. Lek Bojaj

2. Malot Bojaj

3. Mark Ivanaj

4. Gjergj Luca Ivezaj

5. Nikoll Lekocaj

6. Anton Pjetri Sinishtaj

7. Viktor Pjetri Sinishtaj

8. Viktor Luli Dreshaj

9 Gjon Nika Dreshaj

10. Kole Toma Dedvukaj, US citizen

11. Rrok Gjergji Dedvukaj, US citizen

12. Sokol Luca Ivanaj, US citizen

13. Pjeter Frani Dedvukaj

14. Gjon Frani Dedvukaj

15. Zef Kola Dedvukaj

What we do know is this – most of the suspects were either party supporters or candidates to the up-coming national and local elections that were held the very next day.

Most political polls and media forecasts were predicting a sweeping victory for the Albanian parties where they are the majority, and losses to the Montenegrin party in Malёsia would threaten the authoritarian grip Podgorica had on Albanians for so long.

As a result, and immediately following these polls, the vicious arrests took place and most analysts of the events agree were politically motivated.

With victory in the local elections of Tuz, Albanians for the first time will control their own political, social and economic affairs. This created a threat for Podgorica, because up until September 10th, the state controlled all local affairs that Albanians engaged in, for the most part denying Albanians social and political freedoms that are customary throughout Europe. This, according to local analysts, was an opportunity for Podgorica to generate chaos where the state would re-establish its control and influence on all aspects of life in Malёsia.

How soon Podgorica has forgotten that it was the Albanian vote that brought independence to this tiny country. In fact, the number of pro-independence votes in Malёsia alone made all the difference to secure Montenegro’s fate as an independent country.

Today Montenegro has carelessly accused these same people of terrorism, BUT realizes that these allegations are only as true as the motives behind those detained. There are no such motives, for if there were, then the recent visit of Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld on Tuesday would have brought some of these incidents out.

However, in an effort to prove itself as an ally against the war on terror, Djukanovic mentioned nothing to Rumsfeld that Montenegro is undergoing any threats itself, leading to conclude that these accusations may have been premature and unjustifiable.

What Djukanovic did say is that Montenegro was prepared to "accept all responsibilities of a nation to join Europe".

One responsibility that he is not prepared to accept is following international standards on human rights and the protection of ethnic Albanians.

Any chance that Montenegro has to join the family of Europe and make strides toward Euro-Atlantic integration can only be achieved through incorporating its ethnic minorities into the socio-political mainstream and stop what Congressman Tom Lantos (D-CA) recently referred to as “Quiet Ethnic Cleansing” in Montenegro.

By following the historical events in Montenegro throughout the 20th Century and into the 21st, it is clearly apparent that Podgorica has a vision for Albanians, the same vision that guided Slobodan Milosevic all through the 1990s:

1. Montenegro has made the political, social, economic and civil conditions for Albanians so deploring that they are forced to leave their homeland for opportunities abroad. (it should be no wonder why there are more Albanians in Detroit from Montenegro than in all of Montenegro).

2. Any opportunity that Albanians have to advance in society is coupled with their willingness to shed their ethnic culture and assimilate to the Slavic way of life.

This is a dangerous model for building a nation, one that the EU should recognize and address, especially now where we have witnessed a 3rd vision of Montenegro – to brutalize and intimidate an ethnic minority in an effort to introduce fear, confusion and chaos where the state portrays itself as the protector and legitimate actor for the people.

Along with Milosevic, Djukanovic has become the only president to have ever labeled Albanians as terrorists, thus introducing fear within this tiny state where the threat of inter-ethnic conflict and discrimination is all but evident.

The Albanian-American Association “Malёsia e Madhe” of Detroit has done its part and continues to lobby Congress to assess the volatile situation in a region that has been tabooed with ethnic wars, and now with the recent oppression of Albanians in Malёsia, Montenegro is threatening to bring back these ghosts of the past.

The US Congress has taken notice. In a letter to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, Senator Carl Levin (D-MI) and Congressman Sander Levin (D-MI) appealed that…

- “The United States must make clear to Podgorica that we expect them to abide by international standards of human rights, especially the treatment of ethnic minorities”;

- “We urge the Department of State and the new Ambassador to press the government of Podgorica to take concrete steps to ensure the equitable treatment of ethnic Albanians”;

- “The United States has a special responsibility to be an advocate for the rights of Albanians who are subject to discrimination and oppression in their native lands”.

On this day in Detroit, the Albanian-American Association “Malёsia e Madhe” along with 1500 supporters in attendance demand the following:

We appeal to the US government to keep its pressure on Montenegro and demand that theses innocent victims be immediately released and allowed to return home to their families.

We appeal to the European Union to seriously assess the inter-ethnic relations in Montenegro prior to any negotiations on associating Montenegro with the family of Europe.

We appeal to the Montenegrin government to stop tormenting its ethnic Albanians and respect the diversity of its minority population, and a reminder that without its vote would not have become the sovereign state it is today.

We also appeal to Milo Djukanovic to remember the lessons learned from the past 15 years in the Balkans, and that although a peaceful minority brought stability and independence, a disturbed minority can challenge that same stability if not respected.

And finally we appeal to YOU… Albanian-Americans and human rights activist throughout the Diaspora to take a stand and let yourselves be heard, that you will not tolerate the repressive behavior any longer and that we will continue our efforts to rightfully proliferate as an ethnic group and demand that our ancient homeland be free from oppression once and for all!

The Albanian American Association “Malёsia e Madhe” is committed and determined to work diligently and tirelessly until the Montenegrin government stops its discriminatory policies aimed at Albanians and their families, and demand that all imprisoned Albanians be immediately freed.

Victim of State Oppression

Pjeter Berishaj became the latest victim of torture in the hands of Montenegro's special police unit that broke into his home early Saturday morning on September 9th and dragged him out of his bed while choking and beating him on the face and head with clubs and the buts of semi-automatic rifles.

Pjeter Berishaj became the latest victim of torture in the hands of Montenegro's special police unit that broke into his home early Saturday morning on September 9th and dragged him out of his bed while choking and beating him on the face and head with clubs and the buts of semi-automatic rifles.In jail, Pjeter was relentlessly punched, kicked, and spat at without knowing why he was detained. After 48 straight hours of torture he was taken to his village in Malesia and dumped on the street without any explanation of his detention.

Today there are 14 Albanians still detained in Montenegro's prisons for crimes they did not commit, but instead falsely accused of "terrorists acts" by the Montenegrin state. Three of the detainees are American citizens that were in Montenegro visiting their families.

In an interview with Berishaj, he insisted that the police never explained why he was being taken away that Saturday morning, but was insulted the entire time of his incarceration, and was specifically warned that if he spoke out against the tactics of the state that those same masked police units would detain him again.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)